A friend of mine pointed me to this video:

A friend of mine pointed me to this video:

The way the singer takes the time to reassure the guitarist, resonated with me on a very deep level.

I don’t think this clip was actually aired, as it would likely be outside the format, but it fits the topic of “making mistakes” in a beautiful way.

Some time ago I wrote about how to give feedback. It dealt mostly with the “head”-side of things, and not so much the part of the heart. Said in another way: It looked at the what and how, but not so much the why.

After thinking things through some more, I realized I don’t know how to cope with mistakes very well. Basically: I’m not good at dealing with the consequences of my failures.

Just look at some of my strategies:

- I practice very hard

- I don’t publish (e.g. here on this blog) until I’ve reread and rewritten my text half a dozen times

- I don’t perform for others (I play the piano a bit but don’t want to play for others much)

- I avoid the spotlight altogether

Obviously, those are attempts to avoid failure.

But there are other ways:

- I explain that I did not have enough time to properly prepare

- I announce disclaimers up front

And it gets worse:

-

- I find external reasons (anything will do and I will explain why they are valid)

- I find excuses and make them seem bigger than they are

- I straight out blame others

- I get angry at myself

- I get angry at others

- I disconnect

Mistakes, as well as errors or just plain failure, can often be like the proverbial elephant in the room: we all know about it but don’t want to address the topic. Many years ago I checked out the videos by youtuber Chosun Ninja, who addresses the difference of forgetting our mistakes and forgiving ourselves.

If you are in a leadership position (not by assignment but meaning that at least one other person looks to follow your example), chances are that people follow you because you display the ability to learn (growth mindset). This looks at the bigger picture in which mistakes are perfectly fine and an effective way of learning.

Looking for perfection in yourself and those around you comes from a fixed mindset, and isn’t leadership but management: actions and performances need to be as good as they can be, and mistakes are deviations and not desired.

Leading is good for people, management is good for the braking system in my car.

In order to learn from our mistakes, we have to take the time to think about them ourselves, pray about it, talk about them with those who love us. All that comes from being honest with yourself.

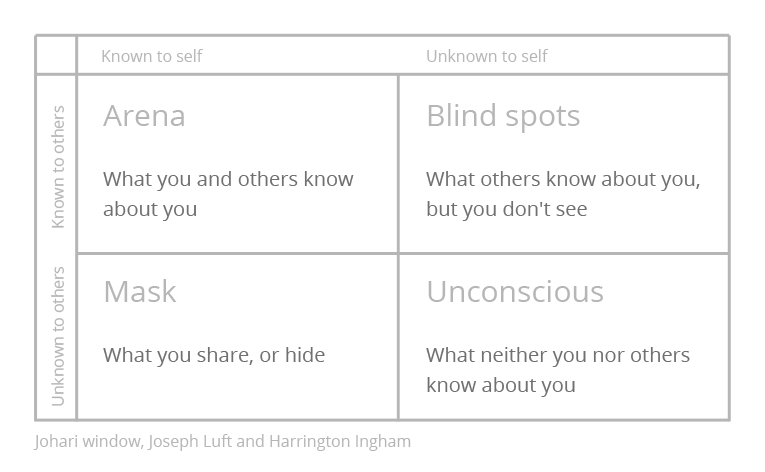

Joseph Luft and Harrington Ingham came up with the Johari window, which neatly acknowledges there’s stuff nobody knows about you, yet.

So, how shall we then live?

At the end of the day, take some time to make up the balance: what went well, what didn’t go well at all. Talk to God about it and ask Him what He thinks about that, and what He thinks of you (spoiler alert: He <3 you). He knows what nobody else knows.

- There is stuff we should notice (because it’s important) but didn’t.

- There is stuff we notice and shouldn’t (because it’s not important).

Periodically, check with your spouse and closest friends about who they think you are. They know your blind spots. It’s your responsibility to allow them to speak into this, and their responsibility to do so honestly and with their best intentions.

Be completely honest with yourself about what you keep from others. There can be very good and valid reasons for that, for example it could depend on your audience who could abuse what they learn, not be mature enough to understand, or you yourself are not ready to share.

But even if you know your reasons are less than noble, be honest about that to at least yourself. If you acknowledge the situation, you can decide if you want to change it.

As you practice this, you’ll experience failure. That’s fine. It’s not supposed to be perfect.